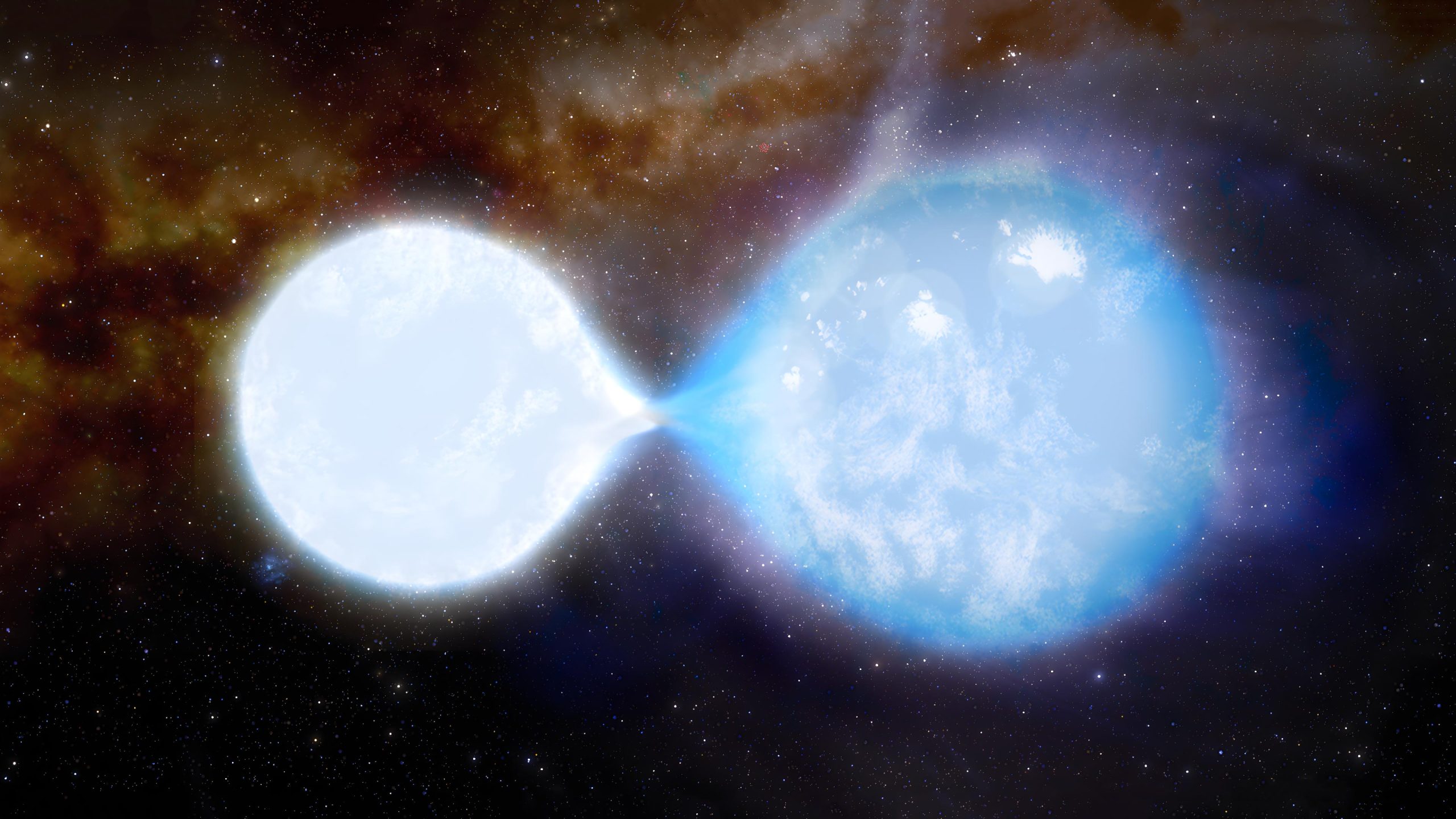

La stella più piccola, più luminosa e più calda (a sinistra), che ha una massa 32 volte quella del nostro Sole, sta attualmente perdendo massa a favore della sua compagna più grande (a destra), che è 55 volte la massa del nostro Sole. Le stelle sono bianche e blu perché sono così calde: rispettivamente 43.000 e 38.000 gradi Kelvin. Credito: UCL/J.daSilva

Un nuovo studio condotto da ricercatori dell’University College di Londra e dell’Università di Potsdam rivela che due massicce stelle di contatto in una galassia vicina stanno per diventare buchi neri che alla fine si scontreranno, generando increspature nel tessuto dello spazio-tempo.

Lo studio è accettato per la pubblicazione sulla rivista Astronomia e astrofisicaha osservato una stella binaria nota (due stelle che orbitano attorno a un centro di gravità reciproco) e ha analizzato la luce stellare ottenuta da una combinazione di telescopi terrestri e spaziali.

I ricercatori hanno scoperto che le stelle, situate in una vicina galassia nana chiamata Piccola Nube di Magellano, sono in parziale contatto e scambiano materiale tra loro, con una stella che attualmente si nutre dell’altra. Orbitano l’una intorno all’altra ogni tre giorni e sono le più grandi stelle di contatto (note come binarie di contatto) osservate fino ad oggi.

Confrontando i risultati delle loro osservazioni con i modelli teorici dell’evoluzione delle stelle binarie, hanno scoperto che nel modello best fit, la stella che viene attualmente alimentata diventerà un buco nero e si nutrirà della sua stella compagna. La stella rimanente diventerà a[{” attribute=””>black hole shortly after.

These black holes will form in only a couple of million years, but will then orbit each other for billions of years before colliding with such force that they will generate gravitational waves – ripples in the fabric of space-time – that could theoretically be detected with instruments on Earth.

PhD student Matthew Rickard (UCL Physics & Astronomy), lead author of the study, said: “Thanks to gravitational wave detectors Virgo and LIGO, dozens of black hole mergers have been detected in the last few years. But so far we have yet to observe stars that are predicted to collapse into black holes of this size and merge in a time scale shorter than or even broadly comparable to the age of the universe.

“Our best-fit model suggests these stars will merge as black holes in 18 billion years. Finding stars on this evolutionary pathway so close to our Milky Way galaxy presents us with an excellent opportunity learn even more about how these black hole binaries form.”

Co-author Daniel Pauli, a PhD student at the University of Potsdam, said: “This binary star is the most massive contact binary observed so far. The smaller, brighter, hotter star, 32 times the mass of the Sun, is currently losing mass to its bigger companion, which has 55 times our Sun’s mass.”

The black holes that astronomers see merge today formed billions of years ago, when the universe had lower levels of iron and other heavier elements. The proportion of these heavy elements has increased as the universe has aged and this makes black hole mergers less likely. This is because stars with a higher proportion of heavier elements have stronger winds and they blow themselves apart sooner.

The well-studied Small Magellanic Cloud, about 210,000 light-years from Earth, has by a quirk of nature about a seventh of the iron and other heavy metal abundances of our own Milky Way galaxy. In this respect, it mimics conditions in the universe’s distant past. But unlike older, more distant galaxies, it is close enough for astronomers to measure the properties of individual and binary stars.

In their study, the researchers measured different bands of light coming from the binary star (spectroscopic analysis), using data obtained over multiple periods of time by instruments on NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope (HST) and the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) on ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Chile, among other telescopes, in wavelengths ranging from ultraviolet to optical to near-infrared.

With this data, the team were able to calculate the radial velocity of the stars – that is, the movement they made towards or away from us – as well as their masses, brightness, temperature and orbits. They then matched these parameters with the best-fit evolutionary model.

Their spectroscopic analysis indicated that much of the outer envelope of the smaller star had been stripped away by its larger companion. They also observed the radius of both stars exceeded their Roche lobe – that is, the region around a star where material is gravitationally bound to that star – confirming that some of the smaller star’s material is overflowing and transferring to the companion star.

Talking through the future evolution of the stars, Rickard explained: “The smaller star will become a black hole first, in as little as 700,000 years, either through a spectacular explosion called a supernova or it may be so massive as to collapse into a black hole with no outward explosion.

“They will be uneasy neighbors for around three million years before the first black hole starts accreting mass from its companion, taking revenge on its companion.”

Pauli, who conducted the modeling work, added: “After only 200,000 years, an instant in astronomical terms, the companion star will collapse into a black hole as well. These two massive stars will continue to orbit each other, going round and round every few days for billions of years.

“Slowly they will lose this orbital energy through the emission of gravitational waves until they orbit each other every few seconds, finally merging together in 18 billion years with a huge release of energy through gravitational waves.”

Reference: “A low-metallicity massive contact binary undergoing slow Case A mass transfer: A detailed spectroscopic and orbital analysis of SSN 7 in NGC 346 in the SMC” by M. J. Rickard and D. Pauli, Accepted, Astronomy & Astrophysics.

DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202346055

“Sottilmente affascinante social mediaholic. Pioniere della musica. Amante di Twitter. Ninja zombie. Nerd del caffè.”

More Stories

I casi di dengue raggiungono i 5,2 milioni nelle Americhe mentre l’epidemia supera il record annuale, afferma l’Organizzazione Panamericana della Sanità

La “Cometa Diavolo” 12P/Pons-Brooks si sta dirigendo verso il Sole. Sopravviverai?

L’Organizzazione Mondiale della Sanità avverte che la crescente diffusione dell’influenza aviaria tra gli esseri umani è “enorme preoccupazione”.